Black Lives Matter and Vayishlach

Black Lives Matter and Vayishlach

14 Kislev 5775

6 December 2014

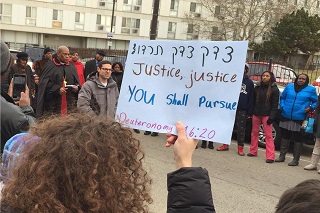

On December 7, 2014, our rabbi and over 30 members of our congregation joined together with others in our community to march with Reverend Dr. L Bernard Jakes and members of the Chicago West Point Missionary Baptist Church in Bronzeville. As Rodfei Zedek (pursuers of justice), we marched together to stand up against racism and to pursue justice for all people.

How are we to understand our namesake as a people, Israel? How do we take Jacob, who was complex and led a fuller life than any other Patriarch, and use his narrative to inform our lives?

How are we to understand our namesake as a people, Israel? How do we take Jacob, who was complex and led a fuller life than any other Patriarch, and use his narrative to inform our lives?

Jacob was deceitful early in his life but then spent 20 years paying for those sins. He was forced to flee his home and homeland, to finally come back to the land of Canaan, only to die in Egypt. God appears to Jacob several times; yet he makes demands of God, he qualifies his beliefs. Jacob demanded that God send him safely back to his homeland, and only then will he be God’s loyal servant. He is not like Abraham; God told him to go and he went. Nor is Jacob's faith like that of Moses, who believed in God but not in himself.

Our parasha opens with Jacob preparing for a possible showdown with his brother Esau. We then see his dramatic encounter with a strange man, whom he wrestles with all night. As the sun rises, this man/being/angel wants to tap out, he wants to released from this struggle. But Jacob requires something in return, and his name is changed to Israel (to struggle with God). The torah calls this being simply eish/man; and we will again see a non-descript eish next week when Joseph is wandering the pasture looking for his brothers and encounters said eish, who tells him where to find them.

We also see Jacob fail as a father with the rape of his daughter Dinah. He waits for his sons to return and does not demonstrate much force of character, or at least the character we know he possesses. After this tragic incident, Jacob’s beloved Rachel dies as she gives birth to Benjamin. At the end of the parasha, we see Jacob reunite with his brother Esau as they bury their father in Kiryat Arba. It is these two reunions that we must take a closer look at today.

The beginning of our parasha gets off to such a dramatic start. The tension is palpable as we see Jacob—not the cocky and deceptive Jacob of his youth nor the quiet and hard-working Jacob we saw last week serving his father-in-law Lavan. But we see a sad and pathetic Jacob, making requests of God and sending half his family off in one direction and the rest in another. We see his calculated language to his servants who will confront Esau and, then, his thought-out interaction with his brother. Despite the years and the long-past trickery, Esau greets Jacob favorably. After Jacob bowed to his brother, Esau ran to him—he hugged and kissed him and was eager to meet all of his relatives whom he had never met. What initially looked like a scene out of West Side Story turns into a Hallmark movie. Esau was gracious and as forgiving as possible, and it is a shame that our tradition has never embraced Esau. It is a shame that our tradition has never held him up as an exemplary model of forgiveness and kindness—but I will return that later.

After the potential showdown ended with tears and hugs, we often think the movie is over; we think they loaded up their caravans and that their father, Isaac, paid for all of them to go a Club Med. That is the way we want to read the story, but it is not the case. The interaction is not over after the warm embrace. Esau tells Jacob that he will give him some of his men and help him back home, but Jacob does not take them nor does he go with Esau. Rather, Jacob demands that Esau accept payments for the pain he caused him and does not take Esau’s help. Esau then goes to Seir while Jacob goes to Schem, and we do not see them together again except at Isaac’s funeral.

At least for me, this is not how I remember the parasha. I remembered their warm embrace and assumed they spent the winter of their lives together before Jacob went down to Egypt. But our parasha paints a much different picture for us, offering us an important awareness into our relationships with the other. So, as we study Parashat Vayishlach in December 2014, what are we looking for? I am looking for some guidance, and I am looking for some wisdom that I have never seen before into the fraught and tense times we are experiencing.

I did not live through the 60s. My experience with that time comes from books and television clips. And I while I was alive for the riots in L.A. in the early 1990s, I did not have an ability to understand the savage beating of Rodney King or what followed. But I am fully aware of the importance of this moment in time. I cannot be silent, but I just do not yet know my words.

Jacob and Esau lead different lives in the parshah leading up to now. They live separately for many years, avoiding one another. Their reunion and embrace shows us the power we hold when we join with brothers and sisters, friends and neighbors, even when what divides us seems impossible to reconcile. If this were where the Torah ended their story, I would not feel better, but it is not.

If you look at Genesis chapter 36, the last in this week’s parasha, it is very possible that you overlooked a crucial line because the chapter consists mostly of a genealogy. The chapter begins by saying, “This is the line of Esau, who is Edom.” This is a terse but hugely important description of Esau since the Edomites in our tradition are equated with the Romans; to be called an Edomite in the Talmud was a tremendous insult. And then we get the kicker in verse six, “Esau took his wives, children and possessions and everything he had gotten in Canaan and went to another land because of his brother Jacob.” Not only did they not spend more time together, but it seems like Jacob paid Esau to leave. Jacob offered him reparations for the damage he had caused and subtly sent Esau on his way.

Our tradition vilifies Esau and his descendants rather than calling Jacob’s character and actions into question. Our tradition and the authors of that tradition found it more important to cast the older brother in a negative light than to take a step back and examine how Esau and his descendants got to the place they were in. Many of the Midrashim that deal with Esau call into question his character based upon his descendants. Very few of the Midrashim demand anything of Jacob; very few ask what could have been different had Jacob treated him better. How could things have been different had Jacob sincerely invited Esau to travel back with him, settling in Canaan together?

Obviously, no one in here choked a black man to death or shot an unarmed black teenager. I am not saying Jacob was a white man and Esau a black man, but I want to use their relationship as a paradigm for discussion. I am not a lawyer or political scientist; that is not my interest. I am not interested in playing judge or jury. My interest is that we talk about this, that we as a community think about how our voice, the voice of Jacob, can be heard. How we can make a difference. Or in the words of a contemporary rabbi who knew something about using his voice, “This is the decision which we have to make: whether our life is to be a pursuit of pleasure or an engagement of service…unless we make it an altar to God, it is to be invaded by demons (Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity, pg. 75).” Heschel understood that Judaism cannot exist in a vacuum. He knew that praying to the God of Israel should not get in the way of our secular and national responsibilities—our Judaism should inform them. Quoting Heschel again, “Judaism is both an assurance and an urge.” The assurance is that we realize the good in life, while the urge is that Judaism becomes attentive and opens our eyes to the world around us.

Obviously, no one in here choked a black man to death or shot an unarmed black teenager. I am not saying Jacob was a white man and Esau a black man, but I want to use their relationship as a paradigm for discussion. I am not a lawyer or political scientist; that is not my interest. I am not interested in playing judge or jury. My interest is that we talk about this, that we as a community think about how our voice, the voice of Jacob, can be heard. How we can make a difference. Or in the words of a contemporary rabbi who knew something about using his voice, “This is the decision which we have to make: whether our life is to be a pursuit of pleasure or an engagement of service…unless we make it an altar to God, it is to be invaded by demons (Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity, pg. 75).” Heschel understood that Judaism cannot exist in a vacuum. He knew that praying to the God of Israel should not get in the way of our secular and national responsibilities—our Judaism should inform them. Quoting Heschel again, “Judaism is both an assurance and an urge.” The assurance is that we realize the good in life, while the urge is that Judaism becomes attentive and opens our eyes to the world around us.

I felt empty Thursday night as I sat watching the Chicago Bears while people gathered in protest for the humanity of others just up Lake Shore Drive from the stadium. I am not telling anyone to go protest; I am not calling on us to change our synagogue’s mission statement. But I am asking that we think about what is our role in these current affairs, where our voice will fall. It is important that the scope of our concerns as a religious community continue to be a dance between the particular and the universal. We always need to be sensitive to this dance because far too many Jews fall out of step with it. I am not looking to trade our garb, abbreviate our prayer, or alter our goals, just to be mindful of our duties as the descendants of Jacob—a line I am proud to be a part of and one that continuously challenges me to be better.

When Jacob had the dream with angels going up and down the ladder, God promised him that he would inherit the land, that God would protect him, and that he would one day return to the land of Canaan. But when he woke up, Jacob repeated the blessing but inserted the word shalom—in peace or wholeness. I believe Jacob was the first Patriarch to truly pray, and in his honor…

When Jacob had the dream with angels going up and down the ladder, God promised him that he would inherit the land, that God would protect him, and that he would one day return to the land of Canaan. But when he woke up, Jacob repeated the blessing but inserted the word shalom—in peace or wholeness. I believe Jacob was the first Patriarch to truly pray, and in his honor…

- I pray that we continue to be a people who inherit the blessings that were once promised to Jacob while struggling with their meanings.

- I pray that we inherit his blessings and good qualities while resisting the urge of our tradition to demonize what we do not know or those we do not understand.

- I pray that justice be served and that we as a people can help find peace and help those around us to be whole.

Rabbi David Minkus

Mon, October 20 2025

28 Tishrei 5786

Upcoming Events

-

Saturday ,

OctOctober 25 , 2025Hybrid Masorti Shabbat Services

Saturday, Oct 25th 9:15a to 11:45a

Join us in person or over Zoom for our Masorti minyan. -

Saturday ,

NovNovember 1 , 2025Na'aseh V'Nishma

Saturday, Nov 1st 10:00a to 11:30a

In the spirit of the words above the Ark in the Simon Sanctuary, "We will do, and then we will listen as we seek to understand," this service broadens our experience for learning and worshipping together. This uplifting, participatory musical service with instruments, facilitated by Cantor Rachel Rosenberg and others, engages us in an experience of worship and learning. Join us for a ruach-filled morning! -

Friday ,

NovNovember 7 , 2025November Kabbalat Shabbat & Potluck 5786

Friday, Nov 7th 6:00p to 8:00p

-

Saturday ,

NovNovember 8 , 2025Hybrid Masorti Shabbat Services

Saturday, Nov 8th 9:15a to 11:45a

Join us in person or over Zoom for our Masorti minyan. -

Saturday ,

NovNovember 15 , 2025Hybrid Masorti Shabbat Services

Saturday, Nov 15th 9:15a to 11:45a

Join us in person or over Zoom for our Masorti minyan.

Quick Links

For Members

Congregation Rodfei Zedek

5200 S Hyde Park Blvd, Chicago IL 60615-4213

773.752.2770 • fax 773.752.0330 • info@rodfei.org

Contact Us • Directions • Calendar • Upcoming events this week

Privacy Settings | Privacy Policy | Member Terms

©2025 All rights reserved. Find out more about ShulCloud